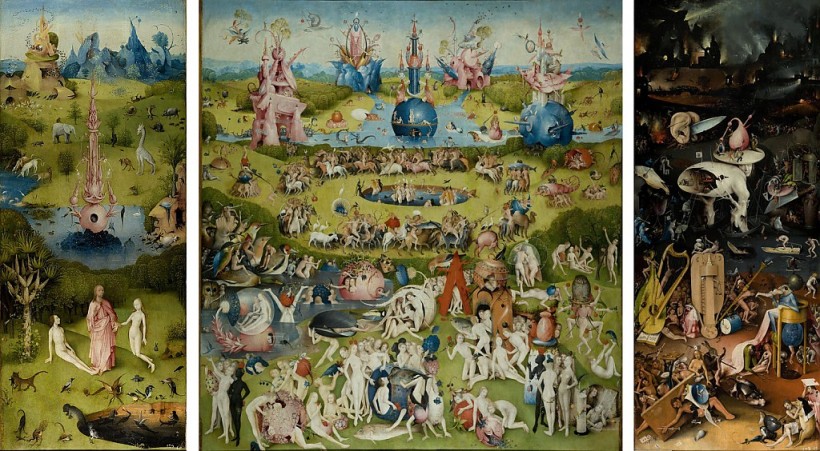

I read this week that Colombian author and Nobel Laureate Gabriel Garcia Marquez did not like when critics described his work as “magical realism.” He thought the line between realism and surrealism is much blurrier. The implication is that “reality” for me, a Cartesian drenched North Atlantic citizen, is much different than that of a Latin American. My “real” is distanced from enchantment that exists in the real world of Latin America. La Mesa embodied this blurring.

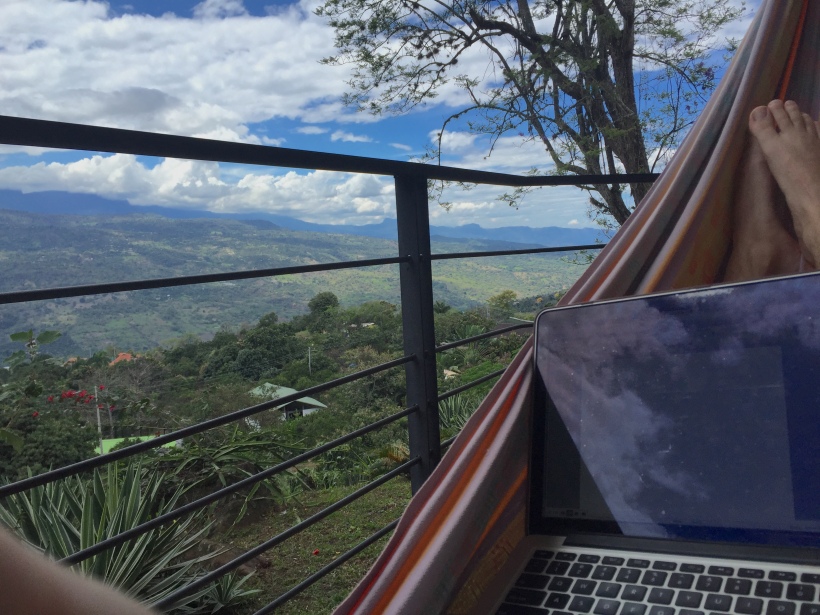

We drove forty miles from Bogotá and descended 6,000 feet to arrive at La Mesa. We stayed at an eco-resort called Hotel Toscana. Our balcony faced southeast. Each morning, Silas would wake-up way too early, around 5:30am, and ask if he could sit in the balcony hammock. Alone, he would contemplate and watch the sunrise, a quality he came by honestly from his Papa Sir. The rest of us would slumber until the warmth would stir us.

By mid-morning the temperature would reach the mid-80’s and a storm would tumble across the eastern range of the Andes. The storms were quick to roll in and quick to roll out. La Mesa would cool for a while, and then heat back up. The rhythm of sunshine and rainstorms seems ordered, but not decipherable by me. Instead of iPhone reminders and Google Calendar alerts, the land dictated our days.

At night, June Bugs would swarm the area. They were like dry leaves in a windstorm, swirling around, bumping into each other. Light pollution from Bogotá seemed mostly obscured by the mountains. One night, I walked by myself around the property and heard footsteps behind me. It was the heavy leaves of a banana tree slapping in the soft breeze.

Another afternoon Silas encouraged Erin and I to come to the porch to see a spider. He said it was in the plant right off our porch. We approached lackadaisically. Of course spiders are neat, but when you are trying to adjust to having three kids, a four-year old’s excitement over a spider is hard to prioritize. I came out expecting some sort of semi-cool jungle spider, but I could not find what Silas’ little eyes had spotted. That was because I was trained to look for a spider, like a normal sized spider. Quickly a tarantula emerged from the plant. On another day we saw a horse suffer and survive a seizure. Erin picked mangoes off the tree for the kids to cut and eat.

Another afternoon Silas encouraged Erin and I to come to the porch to see a spider. He said it was in the plant right off our porch. We approached lackadaisically. Of course spiders are neat, but when you are trying to adjust to having three kids, a four-year old’s excitement over a spider is hard to prioritize. I came out expecting some sort of semi-cool jungle spider, but I could not find what Silas’ little eyes had spotted. That was because I was trained to look for a spider, like a normal sized spider. Quickly a tarantula emerged from the plant. On another day we saw a horse suffer and survive a seizure. Erin picked mangoes off the tree for the kids to cut and eat.

The resort was tucked in a strange neighborhood. It was one part shanty-town, one part private estates. We never got the story of why these two worlds sat on top of each other. I was worried about walking off the resort looking like a couple of dumb gringos with their kids, but I forgot that Erin is not a gringo. We walked along the dirt road, Silas tossing rocks into pools of stagnant water, while Erin exchanged pleasantries with porch sitting locals. We were imposed upon by a pack of barking dogs. I panicked. Erin quickly made a hiss sound, as if she had encountered roaming packs of dogs many times before…because she has. I have often called her my Indiana Jones.

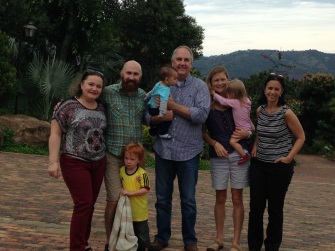

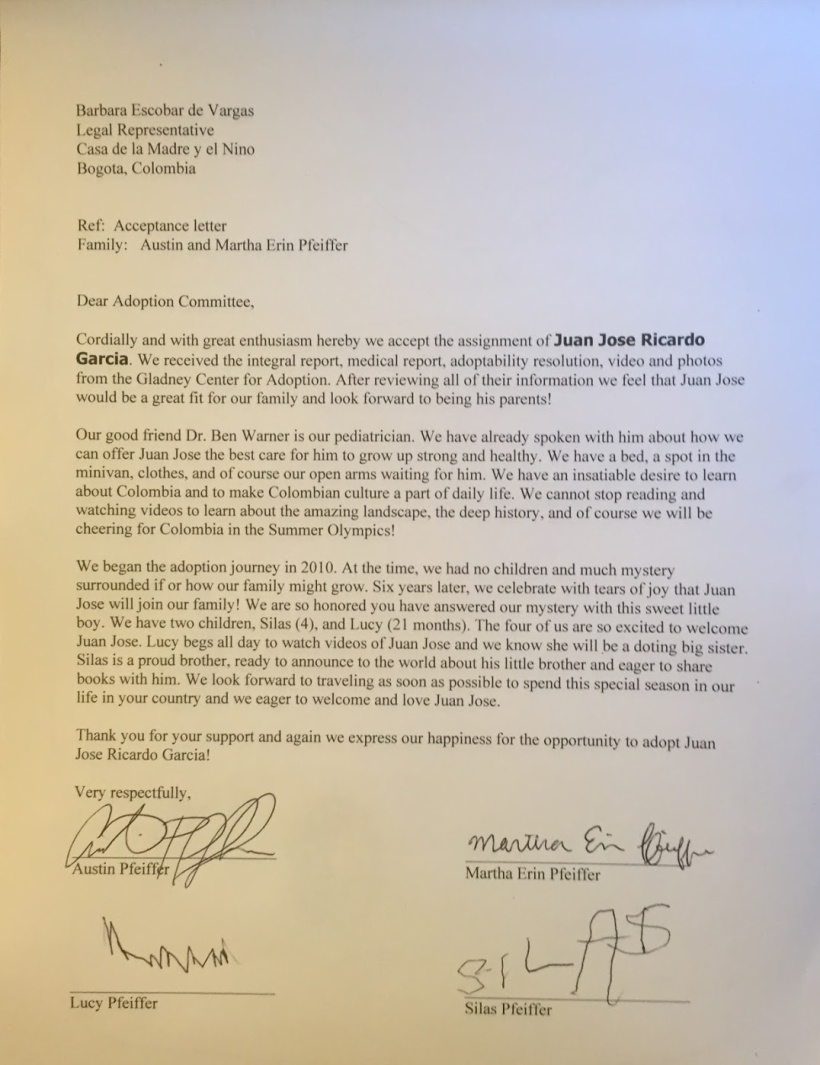

We were in La Mesa for one week, for only one purpose: to meet a judge. Besides the extra time to bond with Marco and observe Colombia, we had the bonus of visiting with some staff from our adoption agency. We met Scott Brown, Executive Vice President at Gladney, and Ella, the Latin America Program Assistant. They happened to be in Colombia at the same time as us. Scott was well known to us from communication over the years, but it was wonderful to get to know him better. Ella is a Colombian who now lives in Texas. Scott gave us a lot of great history on Gladney and Ella taught us a ton about Colombia. Again, we cannot recommend Gladney more!

We were in La Mesa for one week, for only one purpose: to meet a judge. Besides the extra time to bond with Marco and observe Colombia, we had the bonus of visiting with some staff from our adoption agency. We met Scott Brown, Executive Vice President at Gladney, and Ella, the Latin America Program Assistant. They happened to be in Colombia at the same time as us. Scott was well known to us from communication over the years, but it was wonderful to get to know him better. Ella is a Colombian who now lives in Texas. Scott gave us a lot of great history on Gladney and Ella taught us a ton about Colombia. Again, we cannot recommend Gladney more!

But Friday our business came. We went to the courthouse and watched Jairo tisk, wink, and smirk our way into a faster procedure. When it was time to meet the judge, we walked into the second floor office of a building with Spanish colonial architecture. The windows were open, we could see the bustling marketplace and the yellow/blue/red flags of the town square. The judge played with Lucy and complimented Silas’ hair. She spoke with us for twenty minutes, asking about our jobs, our experience in Colombia, and we asked her about her story. She held Marco and we were never quizzed about our parenting style.

smirk our way into a faster procedure. When it was time to meet the judge, we walked into the second floor office of a building with Spanish colonial architecture. The windows were open, we could see the bustling marketplace and the yellow/blue/red flags of the town square. The judge played with Lucy and complimented Silas’ hair. She spoke with us for twenty minutes, asking about our jobs, our experience in Colombia, and we asked her about her story. She held Marco and we were never quizzed about our parenting style.

My conditioning to expect a small spider, a cynical court official, or to assume the sound of footsteps would not be banana leaves, revealed how acute is my sense of “reality.” I am romanticizing of course (especially about court officials). There is an enchantment here none-the-less. The enchantment of Latin America is something Erin discovered much before I did. Her season in Argentina, work in Guatemala, many visits to the Dominican, and now Colombia, have informed her affection for this part of the world. I am only beginning to learn. With these affections being stoked, is it any wonder God would bring us a Colombian son? We had no idea what he was doing when we began the adoption process, but now our family is forever tethered to this place. And this gorgeous, mysterious place really is Macondo.

specialized in respiratory issues in the neonatal unit. She would later make a house call and monitor Marco for two hours.

specialized in respiratory issues in the neonatal unit. She would later make a house call and monitor Marco for two hours.

In the original downtown of Bogotá, La Candelaria, we took the kids on a graffiti tour that was fascinating. Side note, I love my wife. The tour guide was a bit shocked by our arrival and I think quite sure we would leave early, but the gang could hang. At one point I snapped a picture of Erin letting Silas play on a defunct playground surrounded by graffiti in a back neighborhood of Bogotá. We learned about biodiversity, deforestation, the clashes over Marxism and Capitalism, and graffiti styles of course.

In the original downtown of Bogotá, La Candelaria, we took the kids on a graffiti tour that was fascinating. Side note, I love my wife. The tour guide was a bit shocked by our arrival and I think quite sure we would leave early, but the gang could hang. At one point I snapped a picture of Erin letting Silas play on a defunct playground surrounded by graffiti in a back neighborhood of Bogotá. We learned about biodiversity, deforestation, the clashes over Marxism and Capitalism, and graffiti styles of course.

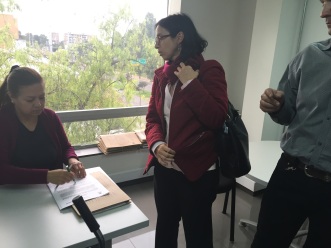

a pit-stop at the Cancillería to have our visas extended. We popped out of Jairo’s car, took an elevator upstairs, and hopped in a short line. To boot, we got to skip ahead on account of our circus of children, stroller, and oxygen tank.

a pit-stop at the Cancillería to have our visas extended. We popped out of Jairo’s car, took an elevator upstairs, and hopped in a short line. To boot, we got to skip ahead on account of our circus of children, stroller, and oxygen tank. So Bruno Mars pulled some strings and let us skip the online form. Again, this was not pity, as I could see on his very stressed face. It was willingness to work with someone he perceived as passing culturally (not me). So he sent us out to the waiting room, then brought us back to his cubicle about thirty minutes later. He looked over our passports. It was at this point I realized I needed to take this

So Bruno Mars pulled some strings and let us skip the online form. Again, this was not pity, as I could see on his very stressed face. It was willingness to work with someone he perceived as passing culturally (not me). So he sent us out to the waiting room, then brought us back to his cubicle about thirty minutes later. He looked over our passports. It was at this point I realized I needed to take this

Around 4pm we ventured back to the apartment. We had gone nine hours non-stop.

Around 4pm we ventured back to the apartment. We had gone nine hours non-stop.

The older kids took out all their familial confusion with some hard play. Lucy did not come away without a face injury, but we all left quite content. We pushed the umbrella stroller across the craggy sidewalks of Bogotá with moderate success.

The older kids took out all their familial confusion with some hard play. Lucy did not come away without a face injury, but we all left quite content. We pushed the umbrella stroller across the craggy sidewalks of Bogotá with moderate success.

limbs. She administers most medicines, though I do have to do the dreaded nebulizer, hold him for vaccinations, and do the night feeding.

limbs. She administers most medicines, though I do have to do the dreaded nebulizer, hold him for vaccinations, and do the night feeding. As you may know, Lucy is my kindred spirit in the family. We are night owls and we are expressive, deep feelers. So my little night owl thespian and I would grab an Ergo and hit the night streets of Bogotá.

As you may know, Lucy is my kindred spirit in the family. We are night owls and we are expressive, deep feelers. So my little night owl thespian and I would grab an Ergo and hit the night streets of Bogotá.  We would watch motorcycles, pedestrians, and we often visited a modern art interpretation of a dog made out of plastic. Upon our return the boys would be resting and Erin would put Lucy down.

We would watch motorcycles, pedestrians, and we often visited a modern art interpretation of a dog made out of plastic. Upon our return the boys would be resting and Erin would put Lucy down.

in his mouth—something for which Julianna prepared us. He had received therapy to work on his mouth skills, but he was still behind the curve. As the soup went from bowl to spoon to mouth to my lap, Erin took notes at a feverish pace. Marco required two inhalers, a nebulizer, a steroid, an antibiotic, a medication for acid reflux, all while on oxygen.

in his mouth—something for which Julianna prepared us. He had received therapy to work on his mouth skills, but he was still behind the curve. As the soup went from bowl to spoon to mouth to my lap, Erin took notes at a feverish pace. Marco required two inhalers, a nebulizer, a steroid, an antibiotic, a medication for acid reflux, all while on oxygen.

Wednesday sounds like “sometime during the day Wednesday.” It was not. Our flight left Raleigh at 6am. We woke-up at 1:45am in Winston-Salem, piled our backpacks, umbrella strolled, pack-n-play (which was been to Guatemala and now Colombia), suitcases, and kids. We picked up Erin’s mom at 2:15am. She graciously drove our car back to Winston-Salem.

Wednesday sounds like “sometime during the day Wednesday.” It was not. Our flight left Raleigh at 6am. We woke-up at 1:45am in Winston-Salem, piled our backpacks, umbrella strolled, pack-n-play (which was been to Guatemala and now Colombia), suitcases, and kids. We picked up Erin’s mom at 2:15am. She graciously drove our car back to Winston-Salem.  We checked-in our circus of gear and made our way to a plane to Miami. From Miami we flew to Bogotá.

We checked-in our circus of gear and made our way to a plane to Miami. From Miami we flew to Bogotá. We arrived at our apartment around 3pm, too early to move-in. So we ditched our bags in a back room and wandered through Parque de la 93, our chic Bogotá locality. It is cosmopolitan with playgrounds, a beautiful green space, coffee shops, boutiques, and a sort of Whole Foods-inspired tienda. It felt like Paris or Manhattan.

We arrived at our apartment around 3pm, too early to move-in. So we ditched our bags in a back room and wandered through Parque de la 93, our chic Bogotá locality. It is cosmopolitan with playgrounds, a beautiful green space, coffee shops, boutiques, and a sort of Whole Foods-inspired tienda. It felt like Paris or Manhattan.

into a monastery for seven months after he realized he was writing, lecturing, but failing to simply spend time in prayer. Barnes describes Nouwen’s situation as, “complaining about all the demands on his schedule, [yet] he paradoxically found himself afraid to be alone.”¹

into a monastery for seven months after he realized he was writing, lecturing, but failing to simply spend time in prayer. Barnes describes Nouwen’s situation as, “complaining about all the demands on his schedule, [yet] he paradoxically found himself afraid to be alone.”¹ Resilient Ministry is more a diagnostic manual, identifying streams of habit and thought and prescribing alternatives to the destructive ones. I am learning about a few of my bad habits. When I wrote to our elders describing my exhaustion, I noted that I do not think my job description is too much work. It fits my gifts and I believe I can accomplish it reasonably. However, three things have led to dysfunction in my work-life.

Resilient Ministry is more a diagnostic manual, identifying streams of habit and thought and prescribing alternatives to the destructive ones. I am learning about a few of my bad habits. When I wrote to our elders describing my exhaustion, I noted that I do not think my job description is too much work. It fits my gifts and I believe I can accomplish it reasonably. However, three things have led to dysfunction in my work-life.

You must be logged in to post a comment.